Home

Perspectives

- A heart is a heart. Or is it?

A heart is a heart. Or is it?

Ms. Pommi, why has women's heart health only come into focus in recent years?

For a long time, medical research believed that there were no differences between the sexes in organs such as the heart. Everyone has a heart, so everything is the same. Therefore, the focus in studies with women was more on the primary and secondary sexual organs, such as breast cancer, topics related to childbearing, tumors in the uterus, and so on.

This has been changing over the last ten years, mainly because equality in professional life is also reflected in medicine. The number of female interventional cardiologists and heart surgeons is on the rise. And when studies are led by women, female probands are more often deliberately included. We need the participation of both genders to recognize differences.

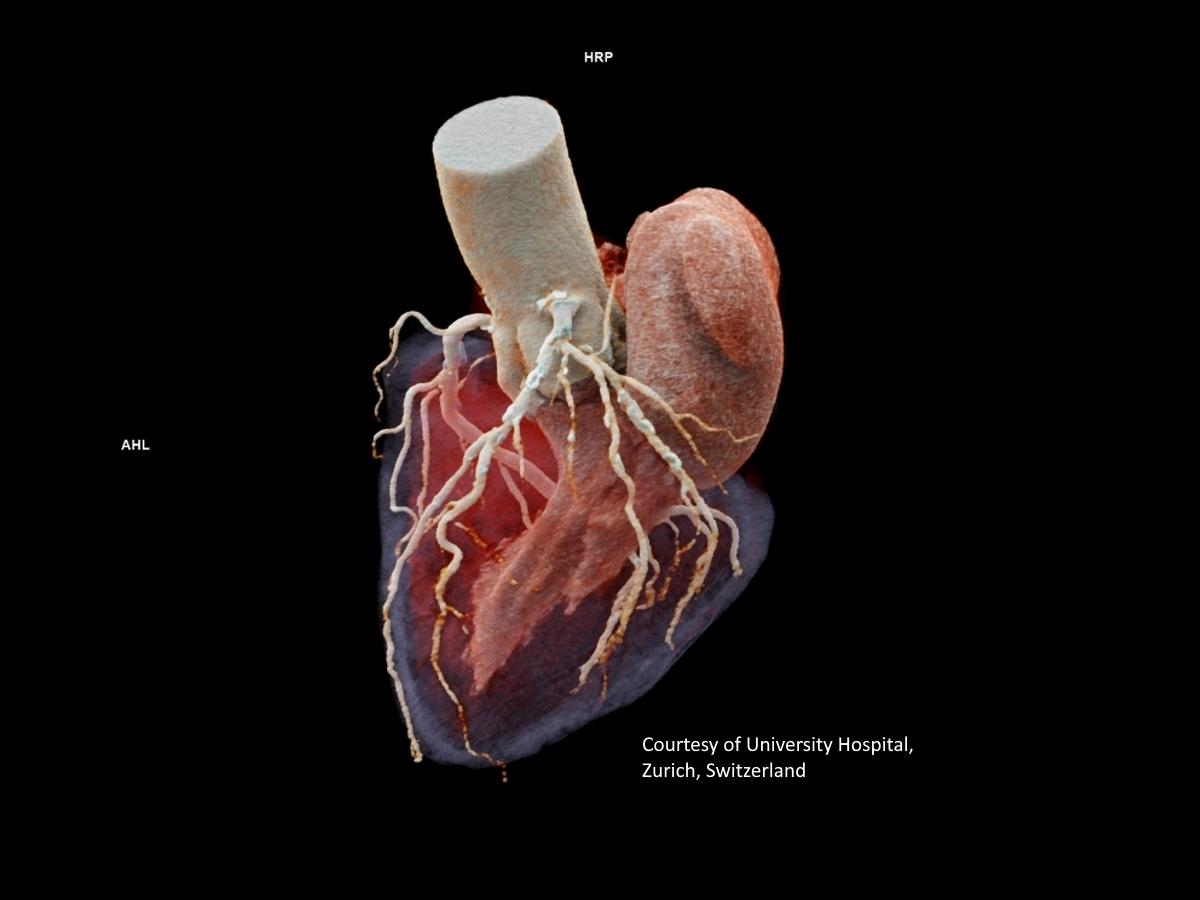

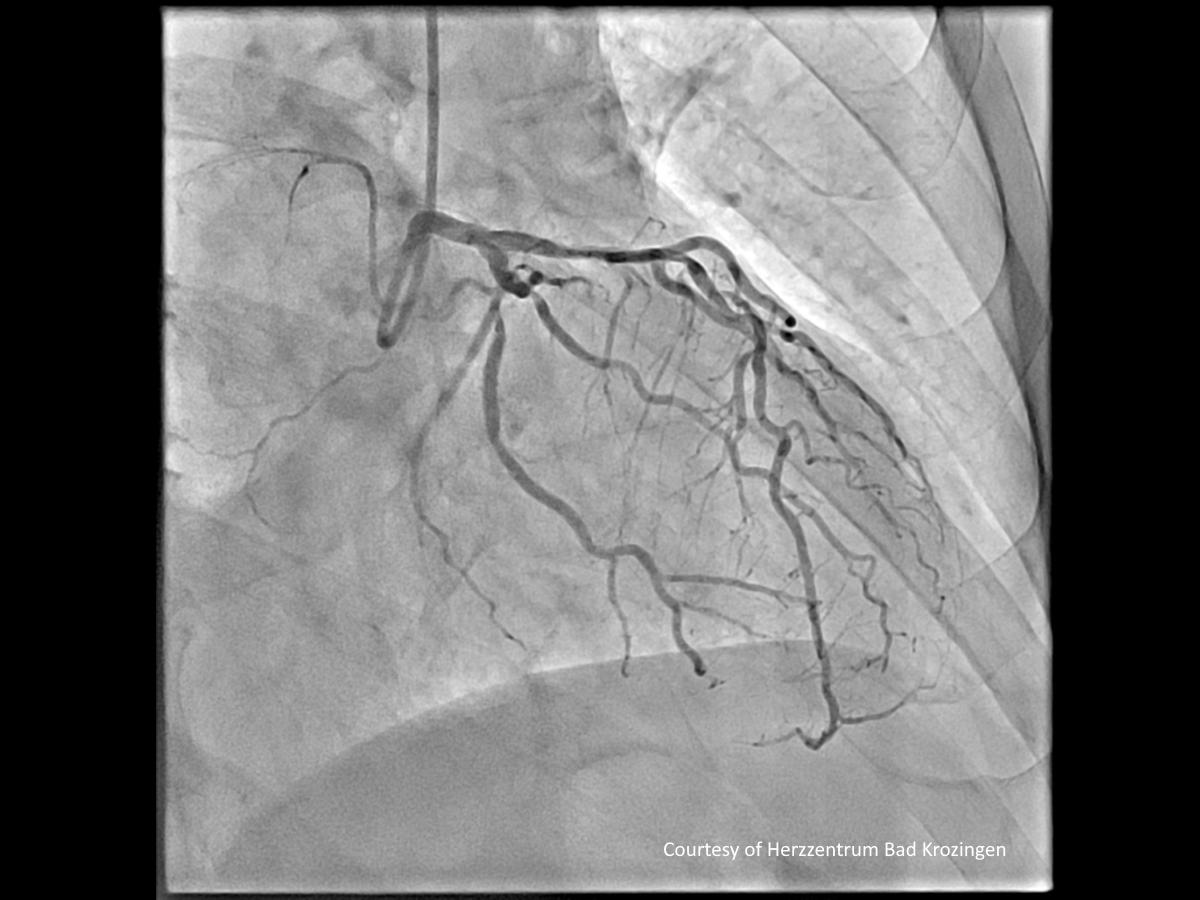

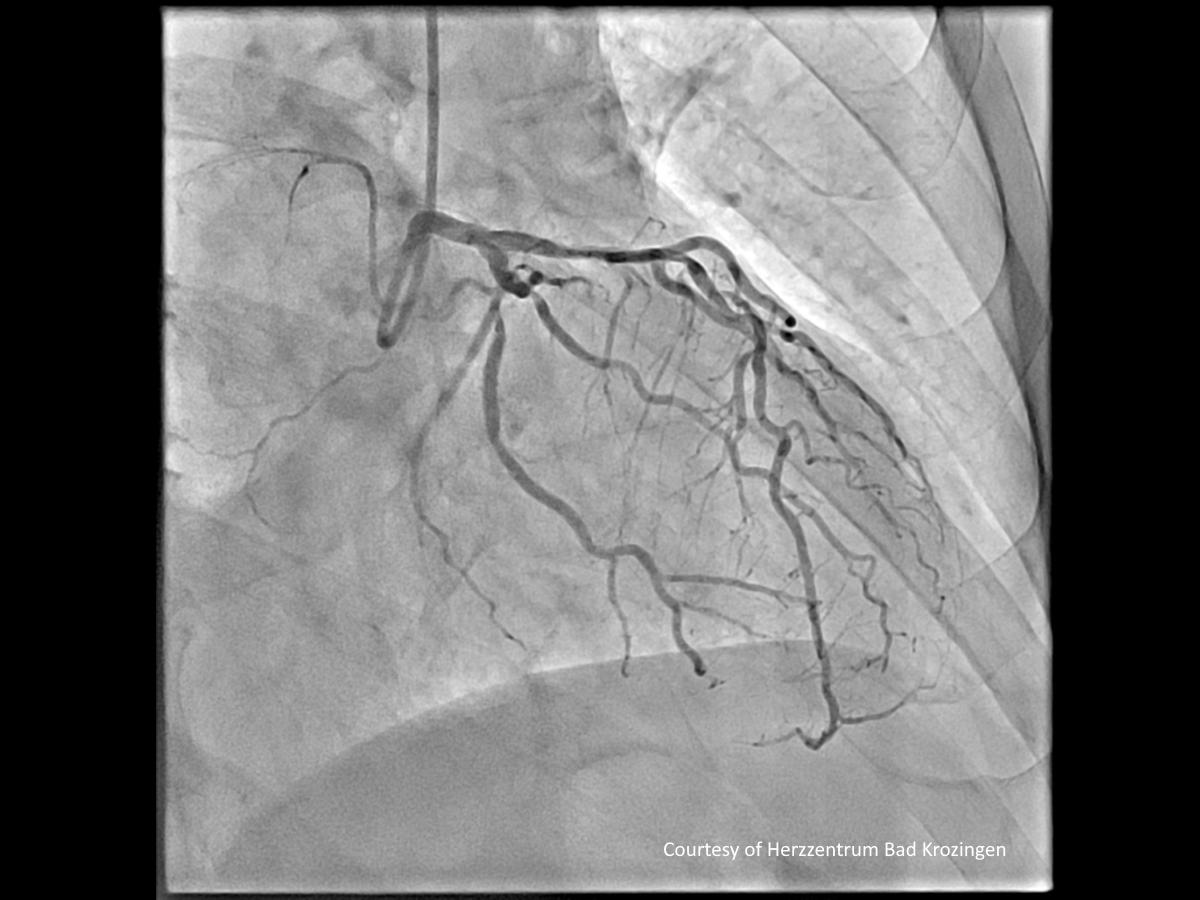

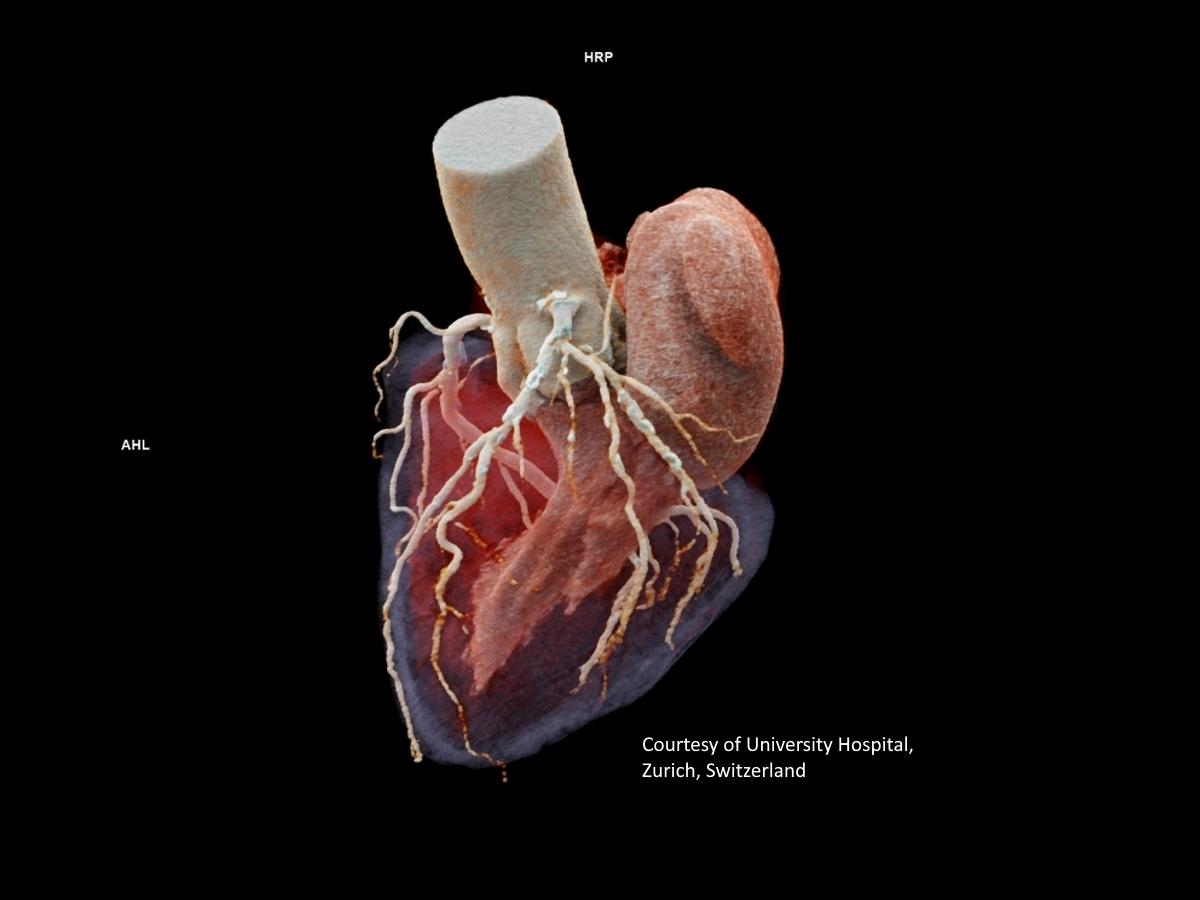

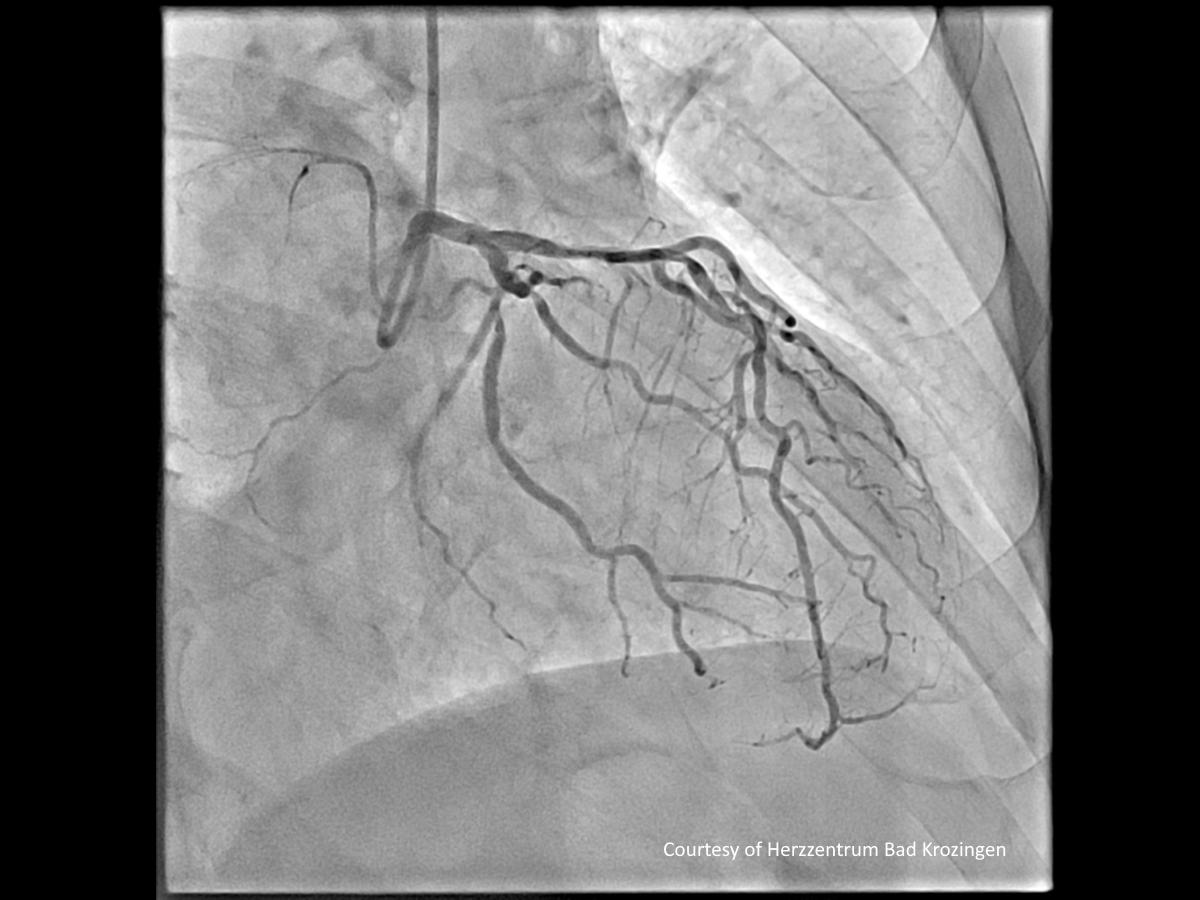

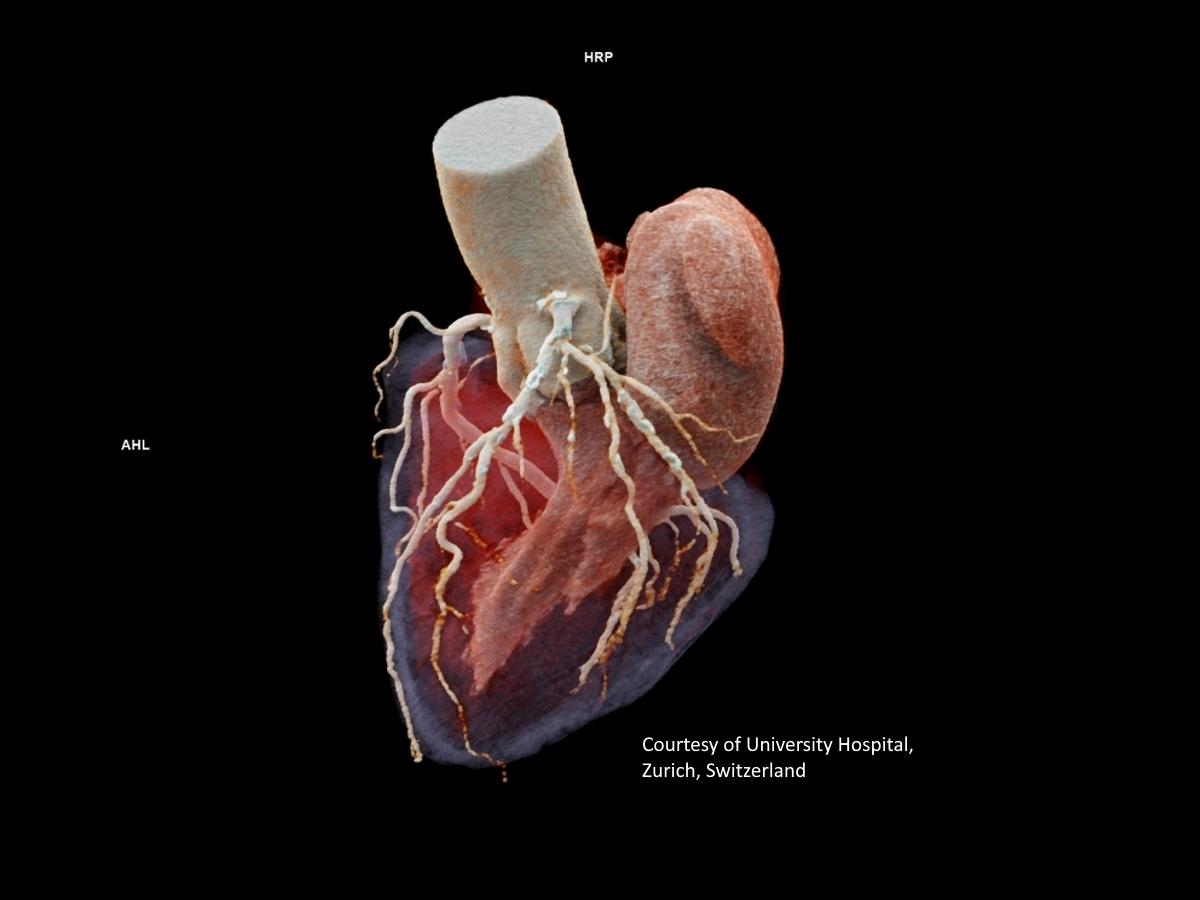

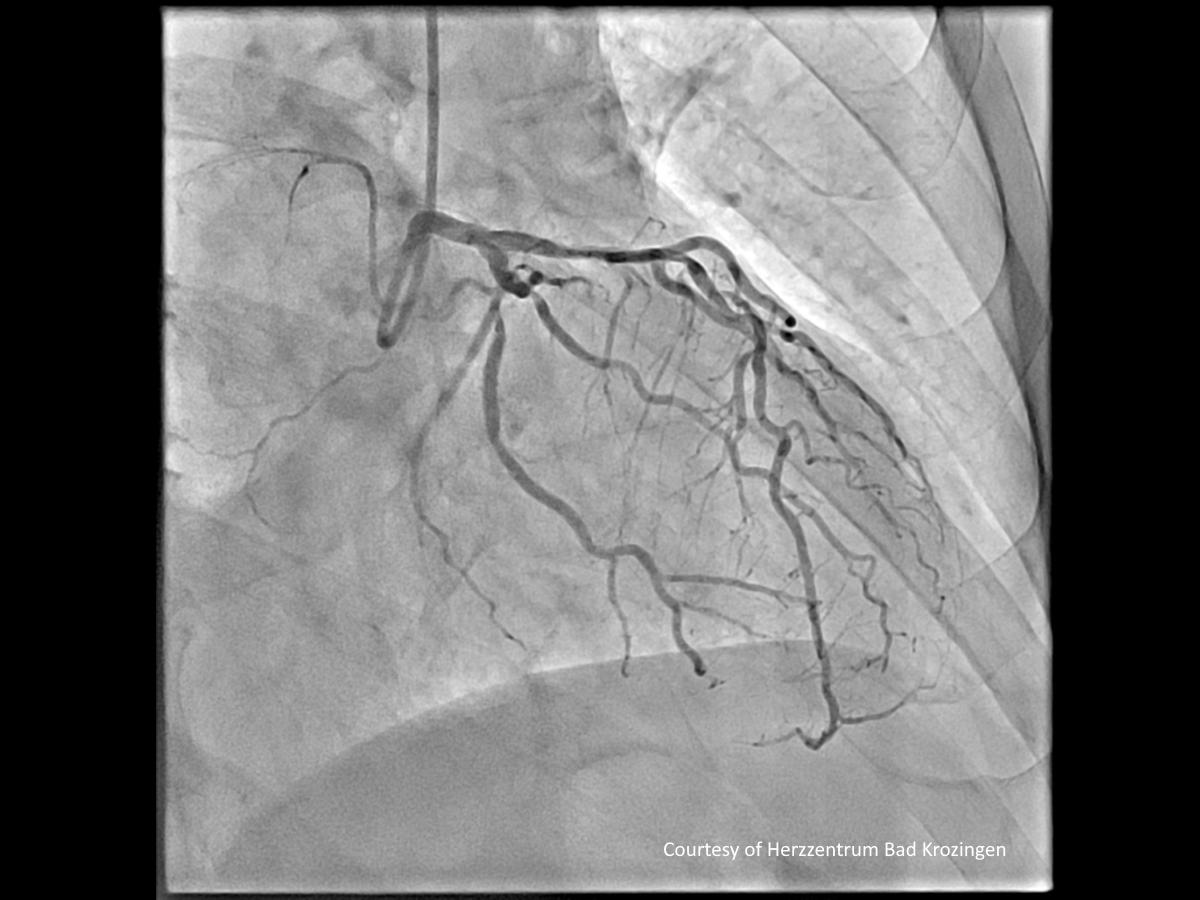

A heart in different imaging methods

From left: Magnetic resonance, Computed tomography (rendered), Ultrasound, Angiography

So clinical trials involving women can be more complex?

Yes, that's right. It is more challenging to involve women in studies. There is more variance because of, for example, menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and menopause. But without evaluating their results, we cannot say where female and male patients react in the same way βÄ™ and where the crucial differences are.

The topic of heart health in women has come increasingly into focus, because it has become evident that certain symptoms of heart disease differ between men and women and that the outcomes are different over a certain period.

How does a heart attack manifest itself in women and why is it so often overlooked?

We all know what a heart attack looks like in men: chest pain or discomfort that can spread to the shoulder, arm, or back. Paramedics, doctors, medical staff or even relatives recognize a heart attack relatively quickly.

However, in female patients, the symptoms are not always as specific: back pain, nausea, migraine, shortness of breath, dejection. As a result, their heart attacks often go overlooked. When women do go to the doctor, neither an ECG, CT, nor a blood test for the troponin value may be done because of the non-specific symptoms. Female heart attack patients are sometimes even sent back home. Thankfully, this is improving.

What is a high-sensitivity troponin I test?

A highly sensitive troponin I test is a type of blood test used to diagnose heart conditions such as a heart attack. Troponin is a type of protein found in the heart muscle. When the heart is damaged, for example, because of a heart attack, troponin is released into the bloodstream. Highly sensitive troponin tests are able to detect much smaller amounts of troponin in the blood than conventional tests. This means that they may be able to detect heart damage earlier and are also useful in ruling out a heart attack in people who have symptoms.

Doris Pommi has been with Siemens Healthineers for 21 years and heads the Cardiovascular Care division. Over the last decade, she has been closely observing a trend towards the individualization of diagnosis and therapy of heart disease in women. Thanks to close networking with scientific institutions like the Leipzig Heart Center, Siemens Healthineers can also help shape and improve this development.

What about other heart diseases, especially in women?

In general, women are extremely well equipped hormonally in terms of heart health in the time between the onset of menstruation and shortly before menopause. However, with the onset of menopause, this changes.

Overall, women are more likely to have non-specific symptoms of heart disease, such as shortness of breath or overall declining performance. Because of this, they tend to see a doctor or specialist at a later stage.

What are the consequences?

Delayed treatment of acute events or the lack of clarification of longer-term illnesses such as valve disease in older age means diseases may be at an advanced stage when they are diagnosed. Treatment must then be carried out with medication or alternatively via heart valve surgery or intervention. This introduces new challenges.

What challenges are there specifically for heart valve surgery in women?

In minimally invasive heart valve surgery, a catheter is inserted through the groin. The valve that no longer closes is for example pushed to the side and the new heart valve inserted through the catheter is brought into the correct position with the help of imaging βÄ™ often angiography and ultrasound at the same time. However, these new, artificial heart valves are more geared toward men in terms of size and physiology.

Although there are different sizes of artificial valves, they are generally not fitting for women's hearts. This can cause difficulties with positioning and possibly affect adjacent structures such as the coronary arteries. These issues can then lead to other side effects or outcomes, as various studies also show us. An important prerequisite for implantation is therefore preparation with the correct anatomical measurements.

Did you know?

How does modern imaging help to better detect heart disease in women?

First, the resolution of CT, MRI, and other systems used in cardiac imaging is getting better and better. And very importantly, cardiologists are increasingly supported by algorithms that analyze these images and offer evaluations or expected results. Due to the growing number of cases and the shortage of specialists, this time-saving support and standardization of expertise is very valuable.

A specific challenge with the female heart when compared to the male heart is that the structures are smaller, and changes may also develop more slowly. Therefore, what applies to men cannot be necessarily classified or diagnosed in women. An algorithm can therefore only work properly if it has been trained with a diverse basis of data from patients from all over the world.

Is this the case with algorithms from Siemens Healthineers?

Yes, our innovation departments use a wide variety of data sets from clinics in all countries to train the algorithms. This was not a conscious decision in terms of women's health, but we simply need a global view for our solution. For example, especially in cardiac medicine, diseases and organic changes sometimes only occur in certain patient populations. Overall, such a basis helps individualized medicine, and thus of course also women's health.

What steps should women take to protect their heart health?

So far, there are no concrete screenings for heart disease. But the data shows that it can be beneficial for women in their 40s to have a cardiovascular examination. This can include an ECG, heart ultrasound, and blood tests.

The results of the examinations can be shared with the primary caregiver or cardiologist, who may recommend, for example, lifestyle adjustments. This would help prevent a development that might require drug therapy or even surgery later down the road.

Overall, women can maintain their heart health and prevent many diseases through a healthy lifestyle. This includes, among other things, a well-balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress management.

What role does interdisciplinary care play in cardiac medicine?

It is extremely important that the different disciplines work together. Gynecologists need to know when the heart needs special attention, like during menopause and during cancer treatment. For instance, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and radiation therapy is a common treatment for affected women. However, radiation endangers the heart due to its physical proximity to the breast. Just as chemotherapy can have a negative effect on the heart. These risks were often overlooked in the past. Today, patients are accompanied by cardiology before, during, and after therapy to detect damage at an early stage.

What is radiation therapy?

What developments are cardiologists making toward interdisciplinary care?

Cardiologists now know what kind of influence hormones have on the heart. A positive effect on subsequent cardiologists is also given by the growing number of combined professorships.

For example, we work closely with scientific partners like Sandra Eifert, MD, senior physician at the University Clinic for Cardiac Surgery at the Leipzig Heart Center, Germany. She offers a consultation hour specifically for women with unclear symptoms or ailments. Eifert takes a holistic approach in looking for the potential causes: Is it the heart? Hormone status? Environmental factors? It is about finding the patient the right therapy at the right time.

What is your wish for the future?

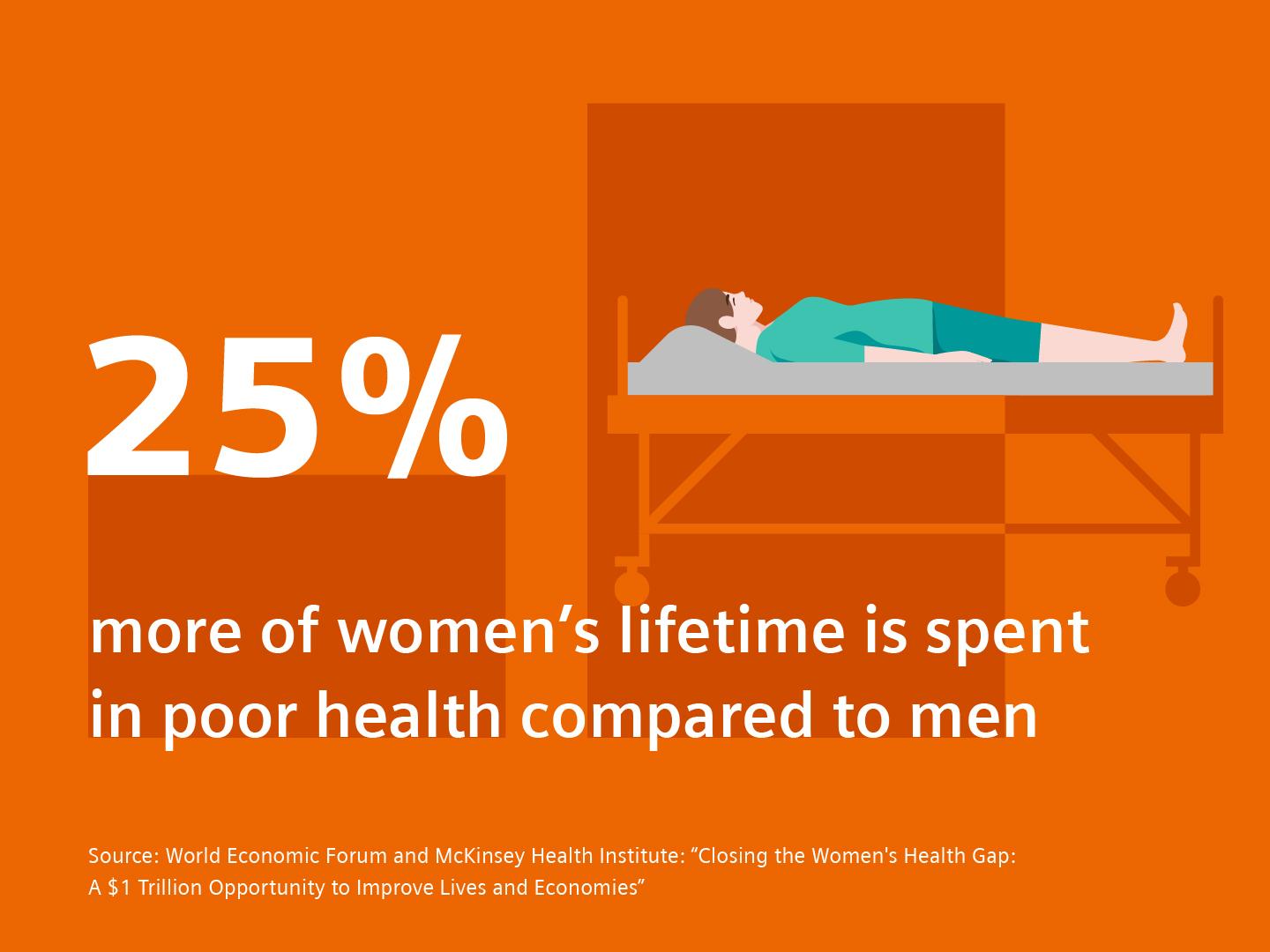

Awareness of the specific symptoms of heart disease in women is very important. I see prevention as a central element as well. To get a holistic picture of a disease, we must continue including women in the scientific studies.

When it comes to solutions, I would like to see a comprehensively trained algorithm that can show us which treatment will bring which outcomes. This could provide a certain standardization, which could help reduce normal human error to a certain extent. This would allow therapy decisions to be adapted according to the patient and their needs. Because every person has a heart βÄ™ but that doesn't mean every heart is the same.

Share this page

Meike Feder is an editor at Siemens Healthineers. She focuses on stories around patient care.

References

[1] World Economic Forum and McKinsey Health Institute: ""